Some of these Things are not like the others

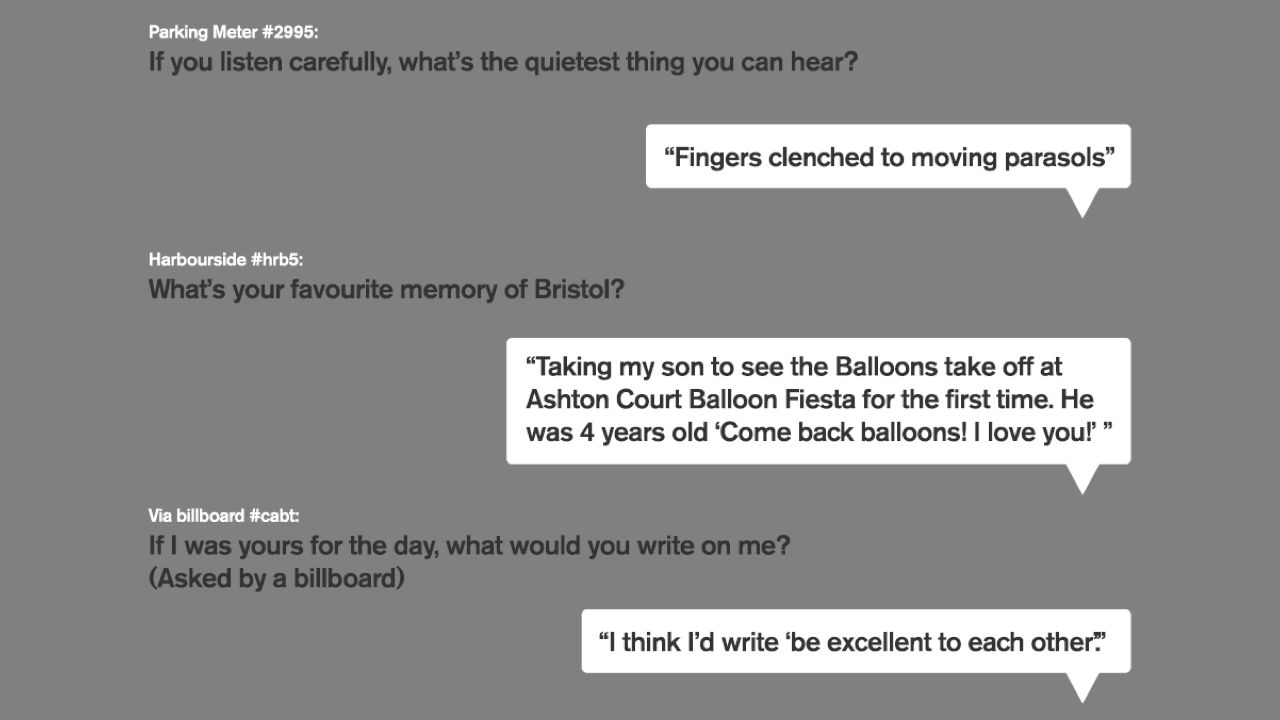

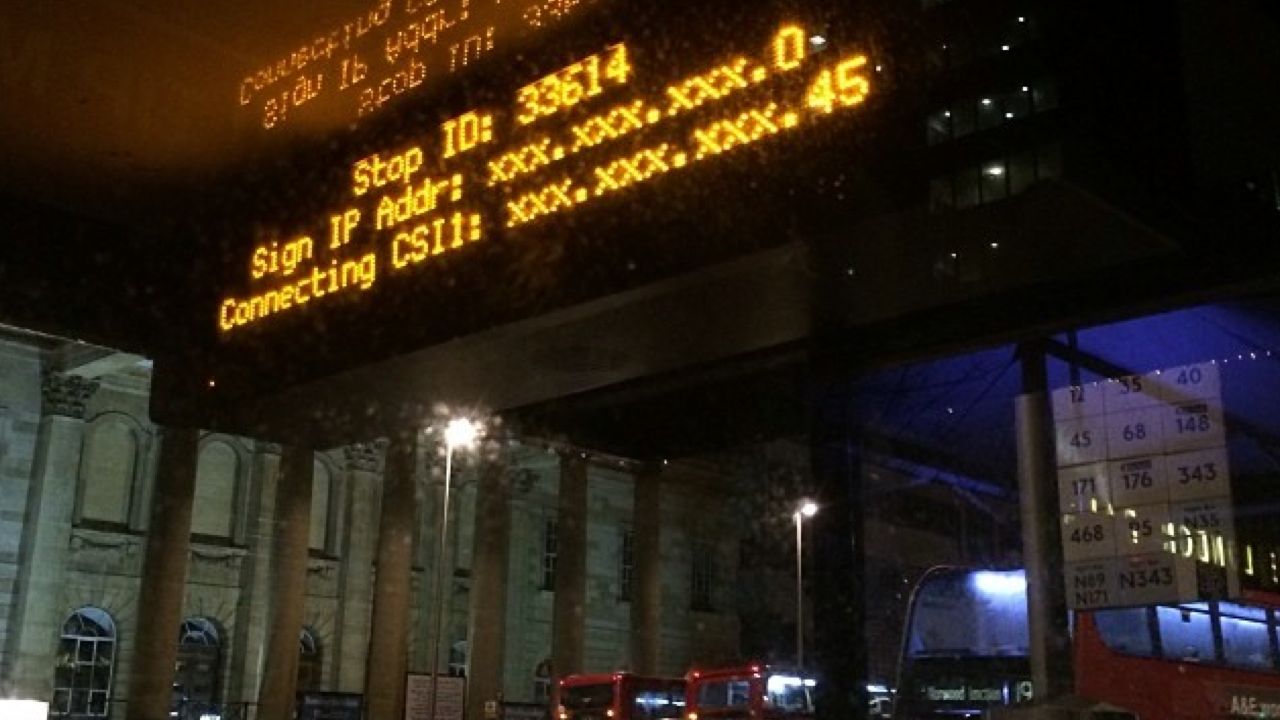

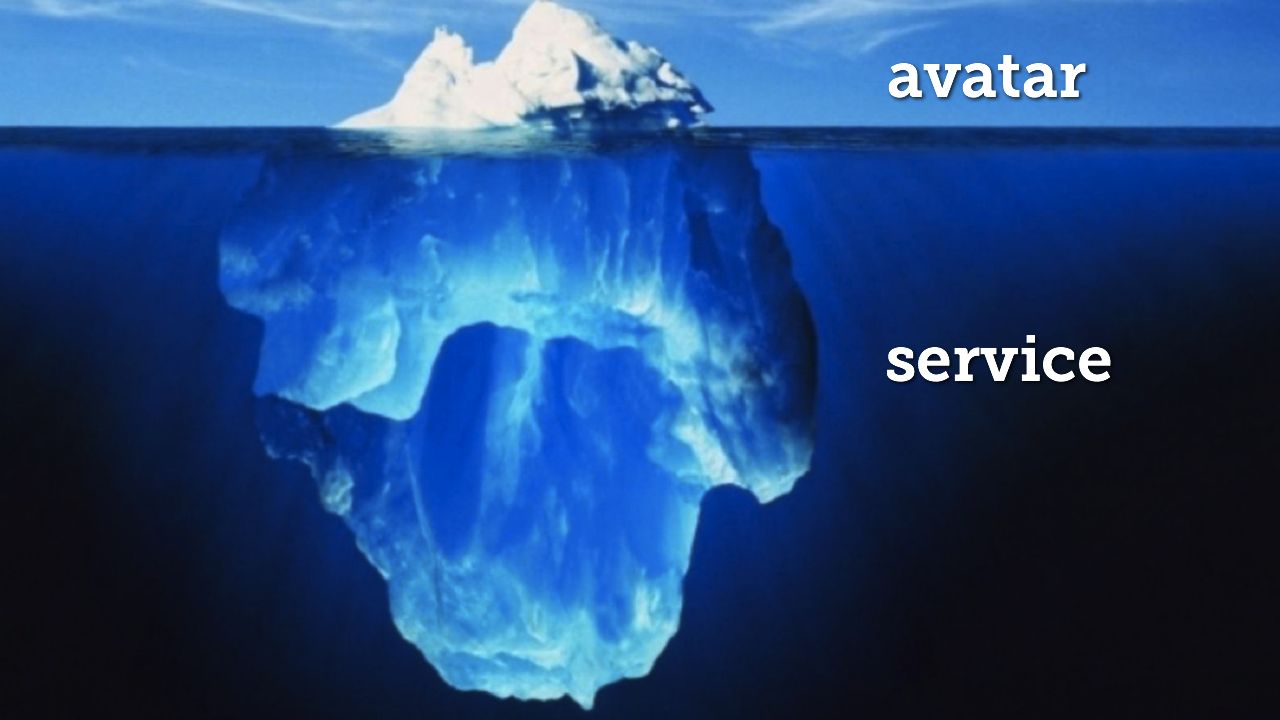

2 December 2014Some of these Things are not like the others was a a talk I gave at Web Directions South, in Sydney, in 2014. It's the last variation of a talk I've been developing over 2014, about connected objects and, specifically, about connected objects for shared and civic usage. I gave a version of this, entitled A Lamppost Is A Thing Too at Solid in the summer of 2014. This is the longest, most complete version of it, and so I've preserved it here, derived from the script I spoke from.

Week 111

1 December 2014Week 111 saw lots of progress on Rubato/Burton. I spent the majority of my time, head town, working through one feature at once.

A lot of the project began from refactoring other people’s code: making the new interactions work with existing data and templates, and then changing the data formats once I realised what I was going to need. As a result, it’s been hard to see the ‘big picture’. I keep having to work through a single feature, get to the end, then come up for air and work out what’s next.

Fortunately, that’s been working well as a process: the number of steps is clear, and I haven’t had to retrace them very often. I’m making the path by walking, essentially. Richard was passing through London on Friday, so he came over to the studio and we worked together a bit – had a chat, and got the code up and running on his laptop.

Before he left, I managed a demo of using the footpedal to advance through steps in a song, with synchronised animation playing out on other screens, and then advancing to a different song using the pedal as well – and the song swapping out on all screens. Which is nearly an end-to-end demo: there’s one big feature left for week 112.

I say this a lot: sometimes it’s hard to see that end goal when I’m in the middle of a particularly hard feature. But the process appears to have worked, and it was great to get to an endpoint at the end of the week.

Otherwise, a few other small issues with another project led to some time spent normalizing somebody else’s messy data, and there were a couple of meetings. I also attended the first meeting of XYZW Club which was really interesting, and some of it even sunk in: I’d upgraded our point renderer to flat triangles shortly after the session.

Week 110

25 November 2014Week 110, and as I returned to GMT, I returned to work.

For a couple of days this week, I worked with George Oates of Good, Form & Spectacle on spelunking a large-ish cultural dataset. The goal was to see what we could prototype in a short period of work – see what was within the data – and also to see what it’d be like working together. It was a fun few days, and we got to an interesting place: a single, interesting interactive visualisation, alongside some broader ‘faceted’ views of the dataset to help us explore it. A nice piece of work, and fun teamwork.

I also kicked off Rubato/Burton, a collaboration with Richard Birkin on building a synchronized visualiser for music, funded by Sound and Music. Richard’s great fun to work with, and the first couple of days on it made great foundations. Firstly, I started writing the foundations of the backend in Node and socket.io; then, porting Richard’s initial work and visualisations over to it.

We had a good early prototype by the end of the week, although one that was going to need considerable iteration in week 111 to support many different songs, and changing songs in a set. Rubato’s the sort of project that requires me to just move one step at a time, though, completing a phase before iterating on it, and so it felt like a good starting point.

I also built Richard a foot controller for it: a couple of momentary footswitches hooked up to a Teensy pretending to be a HID controller. I spent a pleasant morning in the workshop, soldering, drilling, writing some C and packaging this in an aluminium housing, and filmed the lot as part of our documentation.

And, alongside all the code, and design, there was also admin to be done: finalising the 2013-2014 tax return with my accountant.

I’ve got enough to be working on to the end of the calendar year, but I’m looking for work from January 2015. So if you’re interested in working together, or have a project that you think might be a good fit for me, drop me a line. Things I’m particularly interested in: exploring and visualising data; communicating data that through interaction design; projects at early stages that need a prototype, or alpha, or their ideas exploring; connected objects. The sort objects described in weeknotes and projects should give you an idea. And if you’re not sure – why not ask anyway?

Weeks 107-109

25 November 2014

Weeks 107-109 were spent in Australia.

Firstly, at Web Directions South, delivering a talk about Connected Objects (specifically, how to think about designing them, how to learn lessons from them in the design of other things, and how to consider them as more than just objects for individual consumers to own). I think it went well; it’s probably the final refinement of a talk I’ve been iterating on the past year. I hope to get a transcript up of it before the year’s out, and there should also be a video to come.

Then, I took a vacation, because once you’re on the other side of the world, it seems churlish to head back after four days. That was pretty good. I returned in the middle of week 109, and spent the rest of it waiting for my bodyclock to return, too.

Weeks 105-106

28 October 2014A busy couple of weeks. These were the last two weeks in the run up to the delivery of the alpha of Swarmize. That meant lots and lots of small things – all the things you tend to remember in the final few weeks.

Firstly, completing and polishing the documentation. This wasn’t a last-minute thing: it’s been something I spent a while on. As well as some decent enough READMEs throughout the git repository – enough to help other Guardian developers – I also focused on delivering a set of case studies.

You can view them all on the Swarmize site. They cover basic usage and form embedding, advanced-usage (with the storage and retrieval APIs), and a real-world case study. I’m particularly pleased with the use of animated GIFs to explain interactive process – not endless instructions on how to perform a mouse gesture, nor a slow video with interminable narration. I think they’re a really useful fit for documentation.

I tested the API which, after I’d sketched it in Ruby, Graham built a more robust version of in Scala – and removed a few wonky features. That all went pretty smoothly. I also spent a while testing the embeddable forms in a variety of browsers, and learning a lot about

<a href="https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Window.postMessage">postMessage</a>as a result of trying to build a smoother experience in mobile browsers.A few new features also snuck their way in. Dangerous, at the last minute, but they were relatively straightforward to implement and definitely turned out to be worthwhile additions.

And, of course, we spent some time at the Guardian offices demoing it and explaining it. We also got a particularly nice write-up and interview on journalism.co.uk.

I’m hoping to write up my own project page on Swarmize shortly, which will touch a bit more on the process and my involvement (as well as providing a clearer answer than these weeknotes to What It Is).

Some good news regarding Burton: it got some funding. Not a vast amount, but enough to achieve what Richard and I would like to – so that’s going to be a focus before the end of the year. Really looking forward to it.

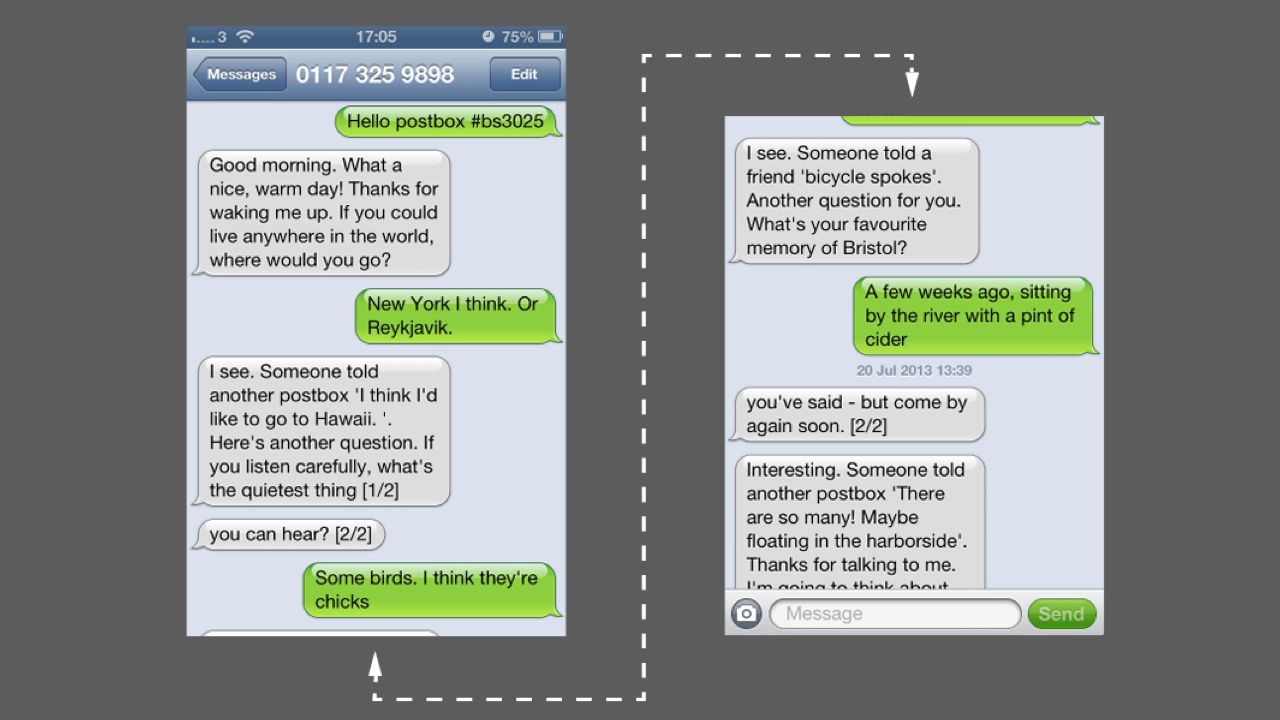

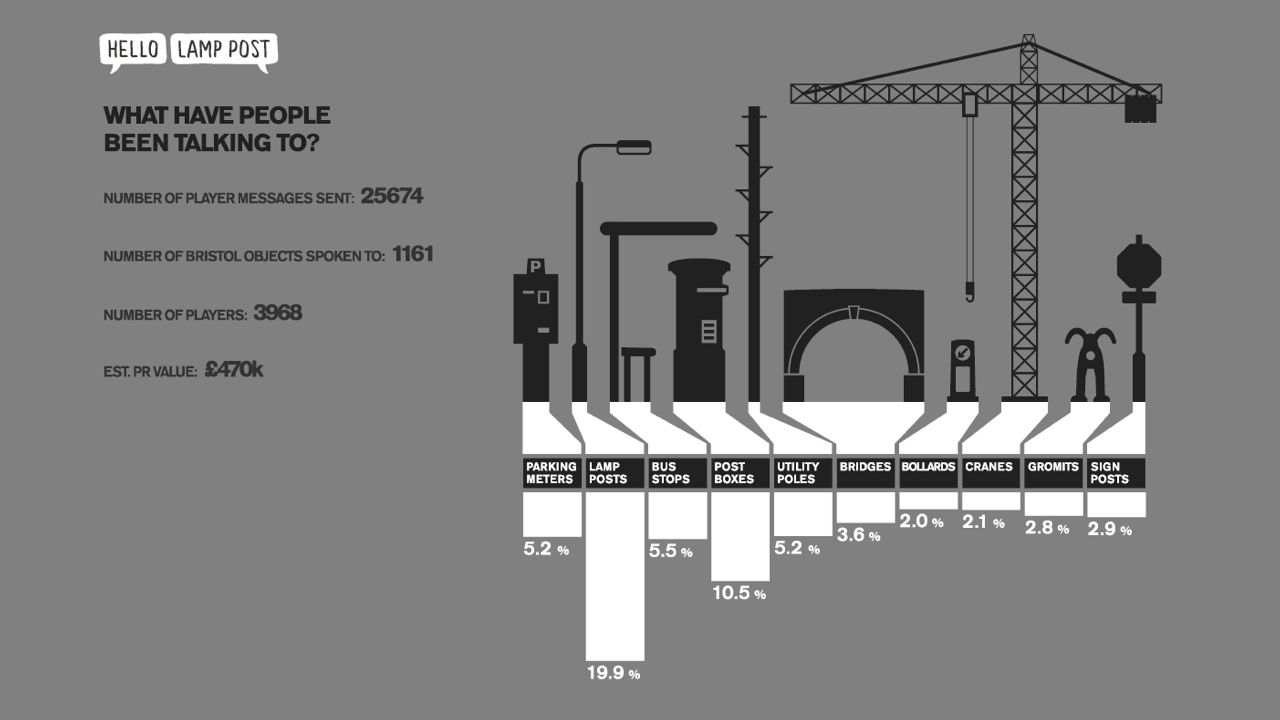

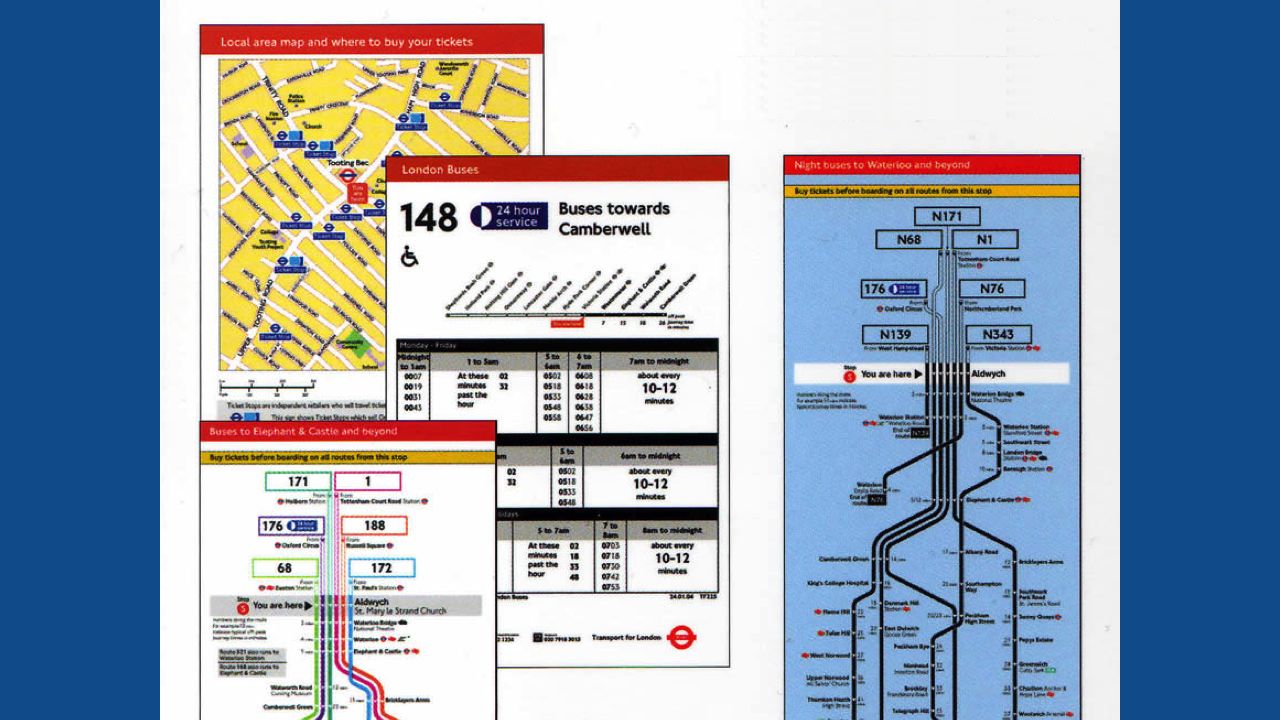

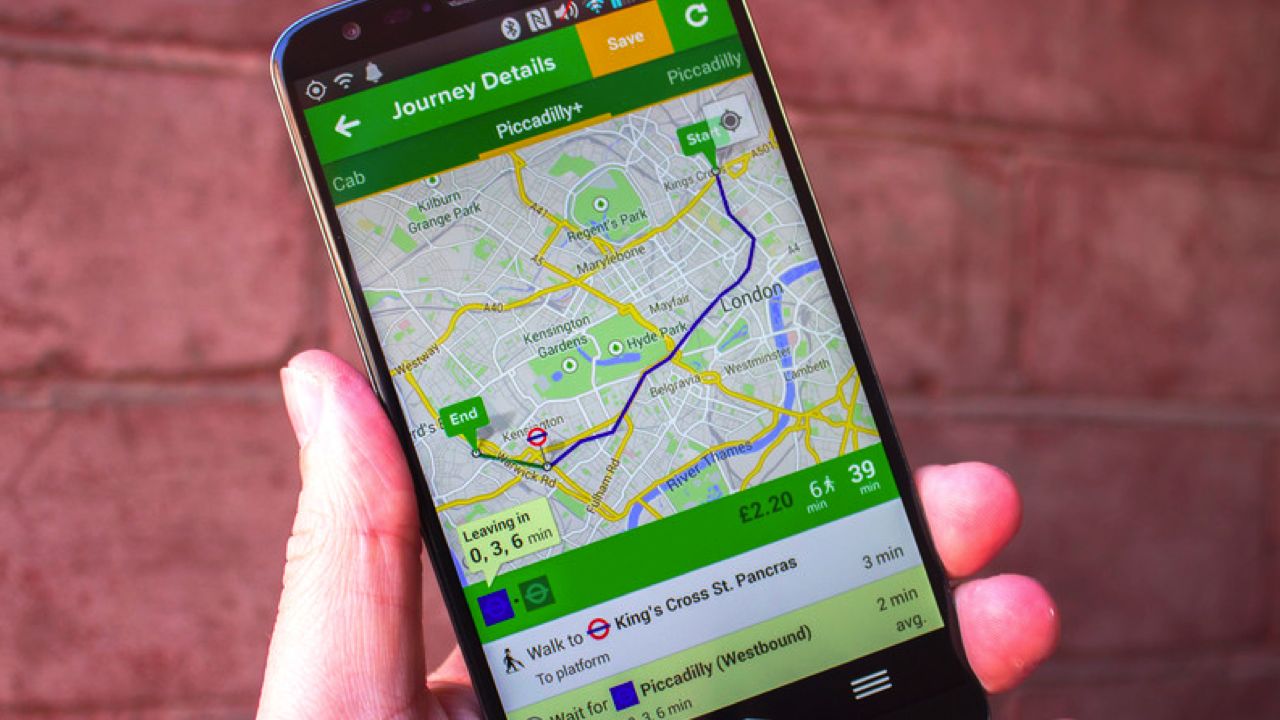

And, finally, I spent a good while working on my talk for Web Directions South. I think that’s all come together reasonably well. Some of these Things are not like the others is an expansion of “A Lamppost Is A Thing Too“, and covers Hello Lamppost, Columba, and various thinking about designing connected objects and services, expanded into a longer, more wide-ranging 45 minute session.

I hope it goes down well. I’ll no doubt have more to say in week 107 – which is going to be spent in Australia.

Week 104

12 October 2014Week 104. Which is 2×52, which means: two years of weeknotes, two years of freelance.

* Blimey. Last year, I wrote yearnotes, and I think I’ll do the same again when I have a bit more space to breathe. Which will likely be on a plane. Suffice to say: I think it’s still going well, and I think I’m going to keep on doing this, and gosh, what I lot I’ve learned and done.

For now, though, focusing on the micro-level:

Week 104 began with rebuilding my server – a VPS I run at Linode. An upgrade to the latest long-term Ubuntu (and necessary patching) led to more maintenance than planned. First, I brought all my PHP websites back up, having found all the compatibility changes in Apache 2.4 from 2.2. Then, onto repairing Ruby, which ended up with me installing the whole Ruby stack again – this time, using rbenv – and rebuilding all the cron jobs for the various software toys I run. With all that done, and all the latest patches applied, I could finally migrate to an SSD-backed Linode. More maintenance than planned, but nothing too heinous – any outage was reasonably short – and I don’t run much that’s mission critical on the VPS. And, of course, now a lot more knowledgable about what’s going on on the server.

On Swarmize/Abberley, I’ve mainly been writing documentation: READMEs for all the component apps, and starting to think about how to explain the project. I’m writing up a few case studies: each focuses on a different facet of the application, and they also serve as documentation for how to use it. I’m illustrating them with screengrabs and, after some experimentation, with animated gifs. I really like animated gifs as a way of explaining software: you get motion, and repetition, but no unnecessary sound, and usually, a few seconds of animation is enough to explain something that might otherwise take a paragraph. Tom Stuart uses them particularly well, for instance.

I’ve also tidied up lots of code: refactored the workflow around making graphs (and made the UI clearer); thrown out some unnecessary things; written an OEmbed provider, as we begin to think about embedding swarm forms elsewhere. The last few weeks of the alpha are all about tidying and explaining, and hopefully they’ll make the few months of weeknotes about Swarmize much clearer!

Finally, I begun the writing and tweaking of my talk for Web Directions South. As usual, it’s hard to pin the talk down – it’s all quite familiar now, and it slips off my brain a bit – but time spent re-familiarizing myself with the topic, getting myself back in the right headspace, is all part of the process, and I’m just going to have to trust the process a bit.

Update: Weeks are indexed from 0, a reader reminds me, so really, week 103 was the end of two years. Week 104 is the beginning of

year[2]. Onwards!Week 103

5 October 2014Week 103 was, I think, a rather good week.

Swarmize/Abberley is moving into its final month before hitting Alpha. The last piece of the puzzle is some kind of API to extract data from the system. We can already put data in, and we’ve got the tools to download and explore it, but what we really need now is a way for developers to extract data programatically: a retrieval API. One we’ve got that, the whole end-to-end process is sketched out.

To that end, I started sketching out an API as a tiny Sinatra application, that Graham will hopefully port to Scala shortly. Within a day or so of work, I had a simple API that allowed exploring of results, overviews of field counts, as well as outputting GeoJSON FeatureCollections given an appropriate location field to pivot around. I’ve started calling this type of code spelunking: diving into a thing to see how it feels, to learn by doing, and trip over myself soon enough that I understand the real demands of the system.

I also sketched out several example applications in flat HTML and node.js-backed client-server apps to illustrate how the API could be used. It’s not enough to just write that code, though: it also needs to be documented. A lot of the week was spent writing clear, concise API documentation, and I’m going to be tidying up all the documentation over the coming weeks. We’re really focusing on everything that will help The Guardian use Swarmize in anger once the alpha is complete.

Pitches for funding for Burton have gone in. I sat down with Richard, who was passing through London on Monday, and talked over various ideas, which were all exciting and productive, and so we hammered some things out in Google Docs – or, at least, Richard hammered most of it out and I offered input where appropriate. Crossing fingers there, but I think we’ll find a way to do something.

And on Friday morning, I brought the film producers I’m mentoring into the studio to sit down and do some drawing. Not a lot, I’ll admit, but it was good to just start showing the process of using your hands to think with and to slow yourself down – forcing you to reason with how much you can fit on a screen, and precisely what needs to be present for a user to interact with. It was useful, and I’m looking forward to seeing how it’s shaped their thinking next week.

Week 102

28 September 2014Back to work after a week off.

That meant diving hard into Abberley/Swarmize. We’d run a test of it around the Scottish Independence Referendum, and now I was working out how to re-implement various features so they’d hold up under the strain of a 90k+ dataset; something that Swarmize is likely to have to deal with.

This meant lots of back and forth, but by Friday night, I’d sussed out how to deliver very large CSV files efficiently – and cache them on Cloudfront for the majority of users.

I also overhauled lots of the real-time updates in the app. These are still fairly straightforward: fundamentally, it’s a traditional HTML-based application, but it’s useful for editors to have live updates.

My homegrown caching routines got thrown out in favour of properly implementing a Backbone-based solution. Backbone has always made conceptual sense, but I’ve never seen a way to implement it into my own work. Thanks to a really useful chat with Nat, something large in my head clicked and I finally saw how to use it in a way I was comfortable with. This led to a big rewrite, and now various graphs and tables are updating themselves in a sensible, sane way.

Other work on it this week: spending some time with Graham overhauling our deployment routines, so rather than reduplicating code, we have a single deploy script that (through configuration) can deploy any component; lots of fixes to code and infrastructure.

The flexibility and general scope of my work on Swarmize has been great, but there are times when it makes me feel pulled in a variety of directions – and right now, that’s hitting a little hard. Fortunately, I ended the week with a long chat with Matt, who’s sponsoring the project, and he helped shape what the next four weeks – to Alpha – looks like in my head. That’s helped set a brief for what we’re doing, and I’m looking forward to writing some burndown lists.

Thursday saw my regular mentoring session for CreateInnovate, where we moved some ideas forward, but it became clear that week 3 would be spent with some pens, drawing: getting thinking out of the head and onto paper, to make it clearer.

I also spent a few hours this week sketching, thinking, and prodding the feasibility of a potential new pitch with a friend I’ve wanted to work with for a while. It feels strong enough that it’s got a codename – Burton – and I’m hoping we’ll find a way to bring it into the world before the year’s out.

Week 101

28 September 2014Holidays are important: they’re important for the head and the heart, and they also tend to make my work better when I return. Week 101 was spent on a proper holiday, in the South of France: no conferences at the beginning or end, no clients prior to work. Just a full week devoted to being on holiday. It was very restorative. Normal service resumes in week 102.

Week 100

17 September 2014Week 100 pulled me in three directions, all of which needed a fair amount of attention to complete before a holiday in week 101.

On the Wednesday, I went to Watershed’s Making the City Playable conference, and delivered a slightly tweaked version of Driftwood. I had lots of great conversations, especially during the Open Sessions, and it was a pleasure to catch up with several friends and colleagues I’d not seen for a while. Sadly, I couldn’t stay for the second day.

I spent Thursday wrapping up Ruardean, delivering wireframes, slides, and a technical brief for the digital component of the theatre show. Hopefully it builds on what Bohdan, Ben and I discussed the week before, and will act as firm foundation for what’s to come. They’re running a Scratch at BAC next week, and they’ll talk a bit about the digital component on the Friday night. (I’m away for week 101, hence shipping early).

And there rest of the week was Swarmize/Abberley. I began the week writing siege-like scripts to bombard Swarmize with results, to get a feel for how the site functioned with a more realistic volume of data. This quickly led to some front-end changes, and also provided the foundation for building a first prototype of time-series graphs.

We integrated a Cloudfront CDN set-up, in order to cache stylesheets and (more importantly) CSV files for completed swarms. I overhauled some out-dated backend code, and worked with Graham on a shared piece of data that affected both the Scala and Ruby apps.

Sadly, the Swarm we were going to run in public during week 101 fell through – but at the very end of the week, another opportunity presented itself, and we focused on rigging things up to make it work. We’re really keen to test Swarmize with live data, and as the first live test runs through week 101, it’ll give us a better of understanding of what to design around – and what the editors work with it need.

A good week 100: lots of balls in the air, and now they need to be caught appropriately in the coming weeks.

Weeks 96-99

9 September 2014It had to happen at some point: the first big lapse in weeknotes. Everything’s been very busy – albeit largely focused on the same thing.

So what’s happened in those weeks?

Primarily: Swarmize/Lewsdon. The past four weeks has seen lots of progress here. After the big demo in week 95, we had another demo in week 96 where we shared the project with editors, journalists, and technical staff – many of whom had seen it at its earliest stages. This led to a variety of features requests and a lot of useful feedback, which we were able to feed into the ongoing work.

The main focus of my development in that time was permissions management – dreary as it may sound, the likelihood that one user and one alone will only work on a Swarm was low. So giving others permissions on them was going to be important – and that meant implementing a permission-granting system.

That also meant confirming that the entire application tested permissions appropriately throughout, and I spent several days knuckling down and writing some controller tests. They’re all a bit verbose, and I’m not sure it’s the best way of achieving this – but it means I have programmatic proof of who can do what, which is important when there’s a boundary between public and private content on the site.

We also spent some time refactoring the configuration of components to be shared between the Rails and various Scala apps. We’ve cut down on duplication a lot as a result.

And, based primarily on editorial feedback, I implemented various fixes to make it easier to edit swarms for minor things – typos and the like – after they’ve launched, as well as offering some more complex edit interactions for developers who want more control.

We’re at the point where we hope to test much of the toolchain in anger in the coming weeks, and I’m really excited about having live data in the system.

It wasn’t just Swarmize in this period, though. Around the August bank holiday I went up to the Peak District for Laptops and Looms, a very informal gathering in Cromford. It was a good few days for the spirit: clear air, good discussions in the morning, good trips in the afternoon, various thoughts provoked. I chatted a bit about making things to make noise with, and whilst it was really just voicing some thoughts on an interest, there were a few notes it hit that I’d like to return to in the coming months – perhaps in another period of quiet. Lovely company, and a good way to revitalise the head. (I also managed to get up Kinder Scout on the Sunday, which was excellent).

Finally, I spent two days in Week 99 working with Bohdan Piasecki and Ben Pacey, developing a digital brief for their theatre/digital work Palimpsest City. Two days of discussion, lots of sketching on playing cards, and whittling down some core details from a big picture. I’ll be writing that up for them in week 100, but it was a delightful two days: thoughtful, intense, and a change of pace and topic from the usual.

In week 100, I’m in Bristol for Making the City Playable, and cranking hard on Swarmize. And, I hope, returning to more regular weeknotes. I always knew there was going to be a blip – and now I know what it looked like.

Making the City Playable, Wednesday 10th September, Bristol

3 September 2014I’m going to be talking at Watershed’s “Making The City Playable“ Conference next week.

I’m going to be speaking alongside Usman Haque and Katz Kiely in a session on Resilience, talking about a variety of the toys, tools and experiences I’ve built around cities and how they re-use and repurpose existing data, systems, and infrastructure. It should be a great event; say hello if you see me there.

Week 95

11 August 2014I’m sat in the Hubbub studio in Utrecht. I’ve been visiting for a few days, and on my final morning, thought I’d catch up with Kars, and borrow a desk to catch up on some email. It’s lovely. A pleasant, cool space with excellent light, and Vechtclub XL (the co-working/studio environment Kars’ studio is part of) is wonderful: lots of makers, craftsfolk, and designers under some very big roofs. I’m a little jealous.

Week 95 was short. I spent it in Newcastle, running a three day workshop for CreateInnovate with David Varela. In that time, we took four pairs of filmmakers through a crash-course in what’s described as ‘cross-media’. I focused on technology and procedural work; David spoke a lot about writing and story, and we both neatly intersected around narrative and games.

It was a busy, exciting three days. We managed to cram a lot in, thanks in particular to some diverse guest speakers Skyping in on Monday afternoon, and thanks also to the enthusiasm of the participants. It’s always exciting to go on a journey with new people, because you never quite know where you’ll end up – and I certainly left with many new ideas, not to mention a broader window onto Film. And, of course, it was a delight to work formally with David for the first time.

The rest of the week was spent out of the studio, visiting friends in Utrecht, and how I come to be in Kars’ studio. Back in the UK, at the Guardian, on the Tuesday of week 96 – and then it all begins again.

Week 94

6 August 2014Another week cranking hard on Lewesdon.

Graham, the other developer on the project, is on a well-earned holiday, so I’ve had two weeks to push the website that most people are going to utilise and experience quite far forward. It’s very much a working wireframe, extending Bootstrap just enough to do what we want, and to understand the pathways through the site. I’m also off the project during week 95, so I was aiming to leave it in a state where he’d be able to pick things up on his end of things – the Scala tools that are going to do some of the crunchier, high performance work.

This week, that meant adding things like authentication – so that Guardian users can log in with their own accounts – and making sure the alpha UI is coherent and functional. I also took some time to write quite a lot of tests, getting the ball rolling for me writing more in future, and also to cover a complex set of functionality: setting the “open” and “close” timestamps for “swarms”, our large-scale surveys. A useful exercise, and it immediately lifted my confidence in my code.

By the end of the week, much of the deck we’d been using to explain the site had been replaced by functioning code: just in time for a demo with the Editor. He was enthusiastic and asked useful, pertinent questions, which we’ve added to the list of editorial feedback. In a couple of weeks, we’ll be showing the work so far to everyone who’s offered us tips.

For the rest of the week, I was prepping for Week 95’s workshop: one large talk and one small to write, along with making sure we had a working timetable. By Friday, I had a decent schedule spreadsheeted up and shared with my collaborators, and a decent draft of my talk about digital media. Come Sunday, I’d be on a train to Newcastle.

Week 93

1 August 2014Week 93 was jam-packed. The majority of it was spent on Swarmize/Lewesdon, hammering out the site’s basic UI. By the end of the week, a lot of the core functionality of the site existed – search was up and working, I’d solved a lot of workflow issues and create an end-to-end of the creation workflow, and integrated all the code from the earlier Sinatra-based spike. Even at this stage, I’ve been understanding the workflows and IA of the project better primarily through the act of making: chipping away at the code to reveal what the product wanted to be all along. Sometimes, that means going backwards to go forwards, but the breakthroughs came in the end, and I was pleased with that.

On Monday, I spent the day with David Varela, planning for the 3-day workshop we’re running in August for CreateInnovate. We came up with a flexible but detailed timetable, a variety of ideas for what we wanted to fit into the workshop, and a coherent structure that ought to help our participants develop their ideas. It was a fun day, and I’m looking forward to delivering the workshop with David.

And on Friday, I spent the day mentoring on the ODI‘s Open Data In Practice course. It was one of the best cohorts for the course yet – the participants all had fascinating backgrounds, and by the end, universal enthusiasm to take what they’d learned back to their day-jobs.

Week 92

21 July 2014A really strong week on Lewesdon/Swarmize, moving closer to a final UI.

That meant a couple of days of staring at markup, Javascript, and the MDN pages for HTML5 drag/drop. I’m building a UI to help editors design a form, dragging fields into it. Drag and drop feels like a sensible paradigm for this, and because I’m building an internal alpha, I’m going to stick to the HTML5 APIs.

We’re building an early alpha, but there’s still a minimum standard of usability to meet, so I spent quite a while working on reducing flickering elements – a bug that emerges because of how drag events propagate through the browser, which makes entire sense if you’re a DOM model, but not much sense to how humans perceive visual elements. Still, some careful work removed almost all the issues here, with a few to solve next week.

I also investigated using Facebook’s React JS to handle the events from the UI and template the form. I was quietly impressed with React: I like that it only really cares about templates and front-end, rather than insisting you build a front-end MVC structure (as Angular or Backbone do).

I stared a lot, but in the end couldn’t see how to apply React to my particular interactions, so I sat down with jQuery, Underscore, and some Underscore templates, and wrote some plain old event-handling Javascript. This turned out to be enough – and quick enough – to get to a satisfying user experience.

I finished up the week building the back-end to store the specification for the form, and then the straightforward server-side templates to generate the form that can be embedded in a web page. I also added a splash of Verify to add some client-side validation. There’ll still be server-side validation, of course, but it feels sensible to maximise the chances of a user submitting useful data to us.

And, finally, I re-used the code from last week to deploy the whole shebang to Elastic Beanstalk and RDS in the final hours of Friday’s working day. I don’t normally deploy on Fridays, but there was no harm done if I didn’t get it done that day, and if I did, it’d be a satisfying conclusion to a busy week.

By the end of the week, UI I’d sketched up as aspirational a few weeks earlier was coming together in its earliest form, and some quick demos at the Guardian got really strong feedback.

So that was a good week on Abberley, and sets up next week nicely.

Week 91

14 July 2014The majority of this week focused on Swarmize/Lewesdon: writing automatic deployment scripts and spelunking code.

I did spend a morning this week with PAN exploring some work they’ve got on the horizon – some discussion of how to approach development, as well as a good table discussion on the design of the project. Always pleasant to work with one’s studiomates, and I’m looking forward to seeing where the project we talked about goes.

Mainly, though it was Abberley/Swarmize this week. Lots of movement here. A lot of that was moving forward a stub of a web application that’s going to be the primary user front-end to it.

I’m not building that application yet, though. I’m building a tiny Sinatra app that talks directly to our ElasticSearch instance to get a feel for the materials: what queries I’m going to need, how to abstract away from a hard-coded single UI, how to get the whole stack up and running.

I took my hard-coded demo and abstracted just enough to make it easy to build a second demonstration on this app. I think that’s the final goal of this code: beyond that, I may as well work on the real thing. I extracted a lot of classes from the big tangle of code, to see where the boundaries between persisted objects for the front-end app, and interfaces to ElasticSearch (and other APIs) would lie.

I also worked on writing deployment code for the app. I’m deploying onto Amazon Elastic Beanstalk, because the whole stack is running on Amazon instances, and I want to play ball with the other developers – and stay inside their security group.

Rather than using the magic of auto-deployment out of git, I’ve been writing deployment code by hand. In part, to understand what’s actually happening – but also because I’m deploying out of a subdirectory, and Amazon’s “magic” code doesn’t play ball with subtrees.

My first pass at this code was a bash script that bundled up a zipfile of the app, pushed it to S3, created a version of the app with that package, and then applied that version to the live environment. I then rewrote it entirely, using the Ruby Fog library, and abstracting out lots of hardcoded variables, the goal being to make it more configurable and adaptable. It also would save time: Fog made it easy to interrogate the existing environments, so the code wouldn’t re-upload a version if it was already on S3, or make a deployment if one wasn’t necessary (which would throw an error, normally).

This took some time, and I began to doubt the utility of it. My doubts went away on Friday, when, with the aid of a few new configuration variables, I pushed the whole lot straight onto the Swarmize AWS account in no time at all. Time spent up-front to save time throughout. And: as a result of that work, I now understand much more about EB as a stack, and how I’ll go on to use it.

As part of that work, I submitted a patch back to Fog – the tiniest, simplest patch – but the pull request was accepted. It’s nice when open source works like everybody tells you it does.

By the end of the week, the end-to-end demo was out of the “rough and ready” version and feeling a lot more polished. I wrapped up the week by researching some Javascript techniques and libraries for Abberley’s front-end, which I’m going to break ground on next week: a Rails app, with its own persistence layer, that’s slowly going to replicate the crude functionality I already have. But to begin with, I’m going to be working out how to make the UI I’ve designed work within it, which I’m rather looking forward to. Week 92 will be a meaty week of HTML and Javascript.

Week 90

6 July 2014Week 90 was busy, but with not a vast amount to report.

Lewesdon pushed forward: getting a fairly good 1.0 set of wireframes; building out a little more of the architecture; really understanding how the thing is going to come together. We’re heading towards a very early end-to-end demo, and I’m hoping that’ll come together in Week 91. This week, though, was spent continuing to chip away: drawing, and coming to understand more about Amazon Elastic Beanstalk.

I spent Thursday and Friday at the BBC Connected Studio for their Natural History Unit, as part of a team put together by Storythings. It was an intensive couple of days, but I think we were all pleased with the pitch we put together, and it was a delight to work with Matt, Darren, Silvia and Stephen. We’ll hear if our pitch was successful later in the month.

Week 89

28 June 2014A quiet week carving away at Lewesdon: working out what it is and what it needs. After last week’s long explanation, there’s not so much to say this week: I’ve just been head down, trying to work out what the product is, moving it forward by writing and drawing.

I’ve described this process as being like pitching myself: telling myself a story, and then listening to see if it makes sense. When it doesn’t, I reframe it. There have been a few useful breakthroughs in my thinking, which usually generate as many questions as answers, but I think that’s good right now. The team are slowly feeling more confident in the ideas I’m putting forward to them, and we’ve begun to ask a few people who are likely to be impacted by the product for initial feedback.

The project I call Lewesdon is, incidentally, Swarmize – a data capture and aggregation platform at the largest scale. The Knight Foundation have now announced the grants, so it’s only reasonable to mention its real name here.

It’s moving forward, and I hope, swiftly enough – but my time leaps between observing, making, observing, making, and it’s tough work to balance it all and not lose momentum.

On Wednesday, a brief meeting set up Blackdown, a three-day workshop for CreateInnovate that I’ll be running alongside David Varela. I mentored briefly on this project last year, and am looking forward to three days with some filmmakers to explore what online projects could do for them. I’m also really looking forward to finally working with David.

But mainly, pushing Lewesdon forward, digging with my Wacom stylus, and pushing onwards.

Speaking at Web Directions South in October 2014

26 June 2014I’m pleased to announce that I’m going to be speaking at Web Directions South, in Sydney in October of this year.

My talk is called What Things Are:

If we’re going to talk about an Internet of Things, we should probably talk about what we mean when we say “thing”.

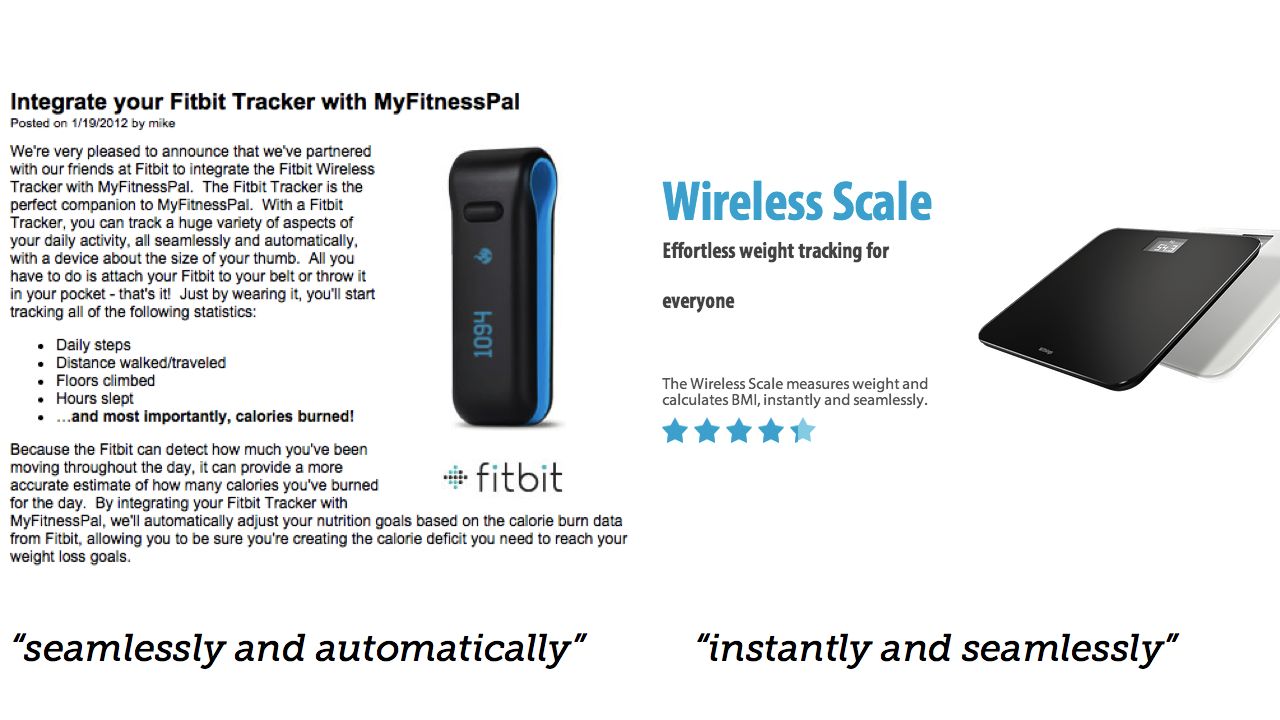

So often, when we talk about the “internet of things” it brings to mind images of consumer white goods with Ethernet sockets or Wifi antennas: thermostats; weighing scales; the apocryphal Internet Fridge.

But that’s a narrow way of thinking that’s perhaps unhelpful: whatever you may think of the term, an “Internet of Things” should embrace the diversity of Thingness.

So what happens when you think about the diversity of things that might be on the internet, and how they might behave? What about Things that people don’t necessarily own, but borrow, share, or inhabit? Through projects that connected bikes, bridges, and a whole city to the network, let’s think about What Things Are – and what they might be.

It’s a longer riff on A Lamppost Is A Thing Too, and is probably the final outing for that train of thought. I’m greatly looking forward to it – it’s a cracking lineup – and I’m flattered that WDS invited me. See you in Sydney in a few months!