Posts tagged as design

Process Notes: Jigs and Things

12 March 2024This is a recent prototype.

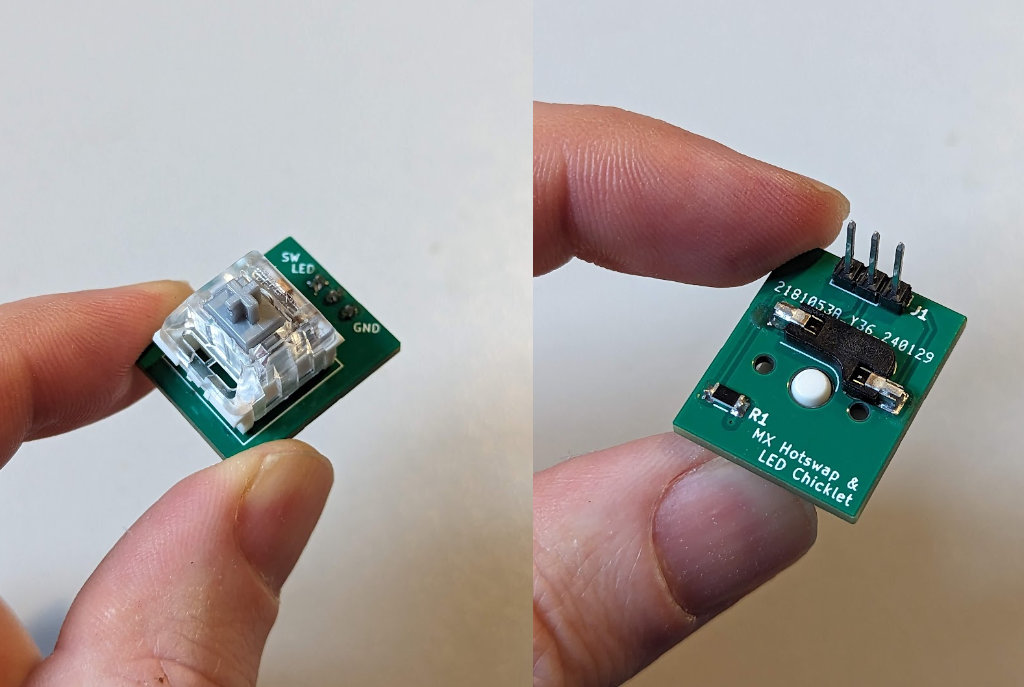

It’s a custom PCB that takes a single Cherry MX style keyswitch, with a resistor and an LED positioned to illuminate the keycap, broken out to pins. That’s it.

It’s part of a larger prototype, that involves buttons and controls and many chips. For a while now I’ve taken to prototyping quite large electronics projects in their full, final form. That means getting a large board made, fully populated with all parts, and then debugging it. It should work first time, but that’s not always the case, and a mistake can mean another costly revision.

This project has more unknowns in it than normal: new parts (like these keyswitches); new ICs; a UI that is still very much up in the air (and involves keys, knobs, and chording). So I’m prototyping it on a breadboard to begin with.

Breadboards often mean a lot of dangling jumper wires and bare components. But making small custom modules like the keyswitch module above can make your life a lot easier. In this case, ten small prototype boards to hold a single key were a few pounds in a recent larger order of PCBs. I’ve used hot-swap sockets so I can re-use the switches themselves in later work. The passive parts and pinheader cost pennies.

But: now I’ve got ten light-up mechanical keys to prototype with, and to reuse in later prototypes.

The keyswitch board is a particular kind of prototype that I build a lot, whether it’s in hardware or software: a small reusable atom, beyond bare wires, but not of use on its own. Crucially: it’s just for me. It might have utility to somebody else, but that’s by coincidence, not design. As a module, it’s not quite like the development boards in my prototyping drawer from firms like Adafruit and Sparkfun. It’s a more low-level building block.

I usually call these kind of things test harnesses or jigs. Here’s another jig, perhaps a more traditional use of the term:

This is a small 3D printed jig that assists me in placing an adhesive rubber foot in the correct spacing away from the corner of an object.

It took a few minutes to design - project the outline of the object, define an offset, extrude upwards, a quick subtraction - and about 15 minutes to print. It does one job, for one particular project, but it made positioning 28 rubber feet quick and repeatable.

Making a thing is usually about also making the tools to make a thing. Test suites; continuous integration; preview renders; alignment jigs. They’re as much part of the process as making the thing itself, and they are objects that show the growing understanding of the current act of making: you have understood the work well enough to know what tool you need next to make it; to know what tool you need next to think with. Making is thinking.

The switch jigs helped me understand how many buttons I’d need, what it’d be like if they could light up, whether it’d be useful to have a ‘partially lit’ state. They also helped me do this work without wasting money on permanently soldered switches. The foot jig came out of need: I had placed enough feet by hand to know that a more professional outcome could be achieved in half an hour of CAD and modelling, time that would be somewhat recovered by the quicker, more professional alignment process.

I love making tools. I particularly love making tools for other people to use and create with. But to only celebrate that kind of toolmaking obscures a more important kind: the ongoing, ephemeral toolmaking that is part of making anything. Making A Tool is not a ‘special’ act; people do it all the time. I think it’s important to celebrate the value of all the tools and jigs and harnesses that are essential to the things we make… and that also are inevitably thrown away or abandoned when the thing they enable comes into the world.

They’re process artefacts: important on the journey, irrelevant at the destination. I have drawers and project boxes and directories and repositories full of them, for all manner of projects - whether they are made of hardware, or software, or ideas, or words. They seemed like a good subject for some Process Notes.

One Thing: Synthstrom Deluge Crash Reports

19 February 2024I was really taken with this, which @scy (Tim Weber) posted on Mastodon the other day:

The Mastodon post is very clear, so to quickly summarize: The device has crashed; it’s shared its stack trace optically, using the LED button matrix on the device. To share that stacktrace with the development team, the end-user only has to post a photograph of it to the development Discord, where an image-analysing bot decodes it and shares the stacktrace line references as hexadecimal. Neat, end-to-end stack-tracing, bridging the gap between one hardware device and the people who develop its firwmare.

This feature is particular to the “community firmware” available for the Deluge. Designed by Synthstrom Audible in New Zealand, the Deluge is a self-contained music device - a ‘groovebox’ - that was originally released in 2016. In 2023, Synthstrom released the firmware for the device as open source, and a community has emerged working on a parallel firmware to the ‘factory’ firmware, with many features and improvements. Synthstrom can concentrate on their core product, and on working on maintaining and improving the hardware; the more malleable part of the device, the firmware, is given to the community to be more malleable.

Why Share This?

Firstly, as the comments in @scy’s original post point out: this is very cool. The crash itself goes from being an irritation to a shareable artefact - look at what this thing can do! I am pretty sure if that if I owned one of these and it crashed, I would share a similar post with friends.

I particularly like it, though, for its transparency. When devices with embedded firmware fail, it can be difficult to work out why, or what has happened - and if the device has no network connection (usually completely understandably!) there’s rarely a way of sharing that with the developer. By contrast, this failure state makes it clear that something has failed and it’s OK to share this fact with the user - because the developer is also asking to be told.

The Deluge makes this reporting even more challenging in one aspect: whilst the Deluge now ships with an OLED screen, original Deluges only have the RGB matrix and a small seven-segment numerical display for output. There’s no way of displaying any text on these earlier models!

But by encoding the stack trace as four binary numbers, it can be displayed on the screen as four 32-bit numbers. Sharing the stacktrace is left to the owner - and can be done with a ubiquitous phone camera. Finally, decoding the stack-trace is the responsibility of the bot in the Discord channel - no need to involve the end-user in that necessarily. The part of this process that runs on the embedded firmware is the least complex part of the process; networking is left up to the user’s phone, and the more computationally complex decoding is left to server-side code.

This feature is also an appropriate choice for the product. Sharing the stack trace to Discord might be a little too involved (or “nerdy”) for some deices, for but for an enthusiast product like the Deluge, with an involved and supportive community, it feels like a great choice.

And it gives the user agency in the emotional journey of a crash. Most of use have clicked “send” on stack traces going to Apple, Microsoft, or Adobe, and then perhaps just given up on the idea that anyone ever sees our crash logs. But here the user is an active participant in the journey: if they choose to share the stacktrace, they have visibility on the fact it’s been seen and decoded in the Discord channel. And now that they’ve shared it to a social space, they have created an artefact to hang future conversation about the crash off - and where they may even learn about future fixes to it.

The feature is neat, and a talking point - but it’s also interesting to see how a moment of software failure can be captured without a network connection on the device, shared, and ultimately socialised. (It also beats the IBM Power On Self-Test Beeps by a long stretch…)

One Thing is an occasional series where I write in depth about a recent link, and what I find specifically interestind about it.

Worknotes: end of 2023 wrap-up

8 January 20242023 was frustratingly fallow, despite all best efforts. Needless to say, not just for me - the technology market has seen lay-offs and funding cutbacks and everything has been squeezed. But after a quiet few months, the end of 2023 got very busy, and there’s been a few different projects going on that I wanted to acknowledge. It looks like these will largely be drawing to a close in early 2024, so I’ll be putting feelers out around February. I reckon. In the meantime, several things going on to close out the year, all at various stages:

Lunar Design Project

After working on the LED interaction test harness for Lunar, I kicked off another slightly larger project with them in the late autumn. It’s a little more of an exploratory design project - looking at ways of representing live data - and that’s going to roll into early 2024. More to say when we have something to show - but for now it’s a real sweetspot for me of code, data, design, and sound.

Web development project “C”

More work in progress here: a contract working on a existing product to deliver some features and integrations for early 2024. Returning to the Ruby landscape for a bit, with a great little team, and a nice solid codebase to build on. Lots of nitty-gritty around integrating with other platforms’ APIs. This is likely to wrap up in early 2024.

This and the Lunar project were primary focuses for November and December 2023.

Nothing Prototyping Project

Kicking off in December, and running into January 2024: a small prototyping project with the folks at Nothing.

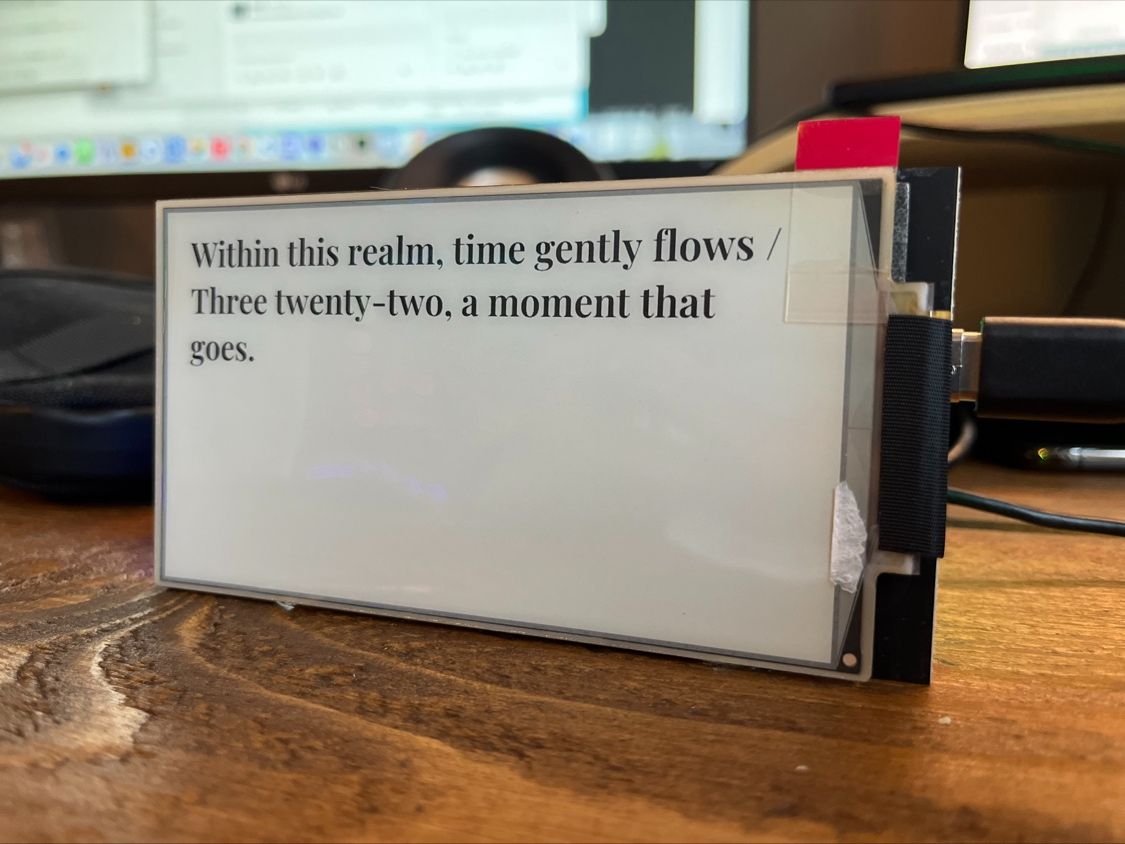

AI Clock

A short piece of work for Matt Webb to get the AI Clock firmware I worked on in the summer up and running on the production hardware platform. The nuances of individual e-ink devices and drivers made for the bulk of the work here. Matt shared the above image of the code running on his hardware at the end of the year; still after all these years of doing this sort of thing, it’s always satisfying to see somebody else pushing your code live successfully.

Four projects made the end of 2023 a real sprint to the finish; the winter break was very welcome. These projects should be coming into land in the coming weeks, which means it’s time start looking at what 2024 really looks like come February.

Announcing “Hello, Lamp Post”

21 January 2013News time! I’m very excited to announce that PAN Studio, in collaboration with myself and Gyorgyi Galik, have been awarded the Playable City Award from Watershed. Full details here.

Hello Lamp Post! invites you to tune in to the secret conversations of the city and communicate through lamp posts, bus stops, post boxes and other street furniture. Part game, part story, anyone will be able to play by texting in a unique code found on the city’s familiar street objects.

…except, of course, there’s a little more going on than that (although not how you might expect it).

It’s a hugely exciting opportunity. I’m particularly keen to see how the initial idea we’ve started from will develop and be honed as we design it, and work with the materials we have – which include both SMS and Bristol itself.

And, of course: it’s worth saying how flattering to be selected from such an excellent shortlist, full of peers and friends.

I’ll save writing any more about the design for the future – and, I hope, in a space with PAN and Gyorgy, where we can share our own insights into the project. Muncaster is go, then. Onwards!

Playable City shortlist announced

14 December 2012I spent a couple of days a few weeks ago working with PAN Studio on their proposal for Watershed’s Playable City project. I’m excited to announce that PAN (working with myself and Gyorgyi Galik) have been shortlisted for the competition, with their project Hello, Lamppost. You can find out more about the project here.

It’s an exciting shortlist – lots of friends, peers, and former colleagues on it – which really captures the breadth of thinking around play in the urban landscape right now. Final results are announced on 21st January; we’ll wait to see what happens next. Congratulations to everyone on the shortlist.

Recent Work: Good Night Lamp

17 October 2012I did a few days working with the Good Night Lamp team this week, on some interaction design explorations. A couple of days of talking, thinking and sketching with Adrian and Alex led to some writing, wireframes, storyboards, and animatics.

Alex asked me to write a bit more about the work, for the Good Night Lamp blog, and there’s now a post over there about it.

Out of all this work, common strands emerged; in particular, a focus on the vocabulary of the product. One of the things I find most important to pin down early in projects – and which design exploration like this helps with a lot – is the naming of things. How are core product concepts communicated to an end-user? How are they made explained? Making sure nomenclature is clear, understandable, and doesn’t raise the wrong associations in a user’s mind, is, for me, a really core part of product design. Even though many of the core concepts of GNL were clear in our head, by sitting down and drawing things out in detail, I started having to discover what to call things, often bringing Alex and Adrian back to my screen to discuss those ideas.

…

This kind of design work initially appears very tactical. It focuses on small areas almost in isolation from one another, exploring the edges and seams of the product. But by forcing oneself to confirm what things are called, confirm what interactions or graphic language are repeated throughout the product, it turns into a much more strategic form of design, which impacts many areas of a product.

You can read more at the Good Night Lamp site. It was a pleasure working with Adrian and Alex. If this kind of work is something you’re looking for, do get in touch.