Driftwood is a talk I gave at

Playark 2013. It was meant to be a talk about leftovers (the theme of the conference being 'reclaim'), and about

Hello Lamp Post. In the writing, it turned into a broader overview of my own work – on six years of projects around cities and play. I was quite pleased with how it turned out, and wanted to share it on the web. (This is a roughly edited version of the script I spoke from).

<p>

<a href="https://vimeo.com/85435067">A video recording of the talk is also available.</a>

</p></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

One of the slogans of the Situationist International was:

</p>

<p>

<em>sous les pavés, la plage:</em> "<em>underneath the paving slabs, the beach.</em>"

</p>

<p>

I tend to read that as meaning something along the lines of: underneath formal infrastructure – that dictates "how to be" – is a space to be free, to play, to be unfettered. The beach is an inherently social place; a place shaped by the people on it, rather than by what it dictates they do. The institutions we erect, for good or ill, sit atop a freer environment.

</p>

<p>

There's a lot of meaning bound up in this; it speaks to lots of things that I think are true, especially when it comes to designing toys, games, and experiences in the urban environment.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

I jokingly referred to a toy I was building as <em>situationist software</em> a few months ago. But now that I've had time to think about this more, situationism turns out to be a useful lens to look with. (Though, it should be noted: I am using it as a lens, not entirely literally. It contains useful ideas, but I'm definitely not embracing its entire political stance – and it is, at its heart, a political and revolutionary framework. So, you know, hoping Guy Debord won't smite me from beyond the grave.)

</p>

<p>

Today, I'm going to draw a line through various games and toys I've built that exist within cities, looking at how they sit atop and alongside other structures or experiences.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

Everything I'll show you has something in common. They're all built out of leftovers: leftover information, leftover infrastructure, old technology, open platforms – the driftwood that washes up on the beach of the city, and that allows us to build new experiences. I'm going to look at what driftwood – the materials we can build from – is, and how some of the ideas propounded by the Situationists help us understand the work of creating experiences for people in cities.

</p>

<p>

The first digital toy I made that expressed some ideas about the urban environment was this: <a href="http://twitter.com/twrbrdg_itself">the Tower Bridge twitterbot.</a>

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

I wrote this in 2008 when I worked right by Tower Bridge in London.

</p>

<p>

It's really simple: it's a little bot on Twitter; it lets you know when the bridge is opening and closing, and for what vessel.

</p>

<p>

It is what you might call barely-software. It's somebody else's data: all the lift times are published weeks in advance online. I just scrape the page with that data on. It's somebody else's platform – I'm just pushing text to Twitter via the API. It relies on several other people's libraries to work. It's primarily leftovers; I've written about 70 lines of code that glues it all together, and runs once a minute on a server.

</p>

<p>

Like a lot of my work, I characterise it as a toy: a small thing that expresses one idea; partly entertainment, but not entirely so; functional, but as a byproduct of its behaviour (after all, all this information was readily available before I built this).

</p>

<p>

But in building it – as is so often the case when you sit down to make something – it began to reveal several interesting truths.

</p>

<p>

For starters: it's a deliberate decision to make it speak in the first person – <em>I am opening for the MV Dixie Queen, which is passing downstream.</em> Why? Because that's what you do on Twitter: you answer the question "<em>What are you doing?</em>" We all speak in first person on it; so should smart devices or buildings. Once it began speaking like us, it illustrated clearly – to me – how Twitter could be a messaging bus for more than just people, but for all the things and platforms in my life.

</p>

<p>

By placing it into the same context as friends and other services, the Bridge told me more than just about its functionality. It became a heartbeat for the city, showing me how often it opened and closed, letting me imagine how often people sat in queues on it, or waited patiently at the large blue gate on the footpath. Even when I couldn't see it, it reminded me how the city I lived in worked.

</p>

<p>

And as a result, not just for me, but for my friends, it became curiously evocative – not just a functional tool, but a powerfully emotive one too. When visiting family, or overseas, it reminds me that London is still there, still ticking away with mechanical precision. This little piece of software had become synecdoche for the whole city.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

It taps into what situationist Guy Debord described as <strong>psychogeography</strong>

</p>

<blockquote>

<p>

The study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals.

</p>

</blockquote>

<p>

Or, more plainly: the relationship between "place" and our understanding of the world.

</p>

<p>

I have two small toys I've built in the past couple of years that are more explicitly and deliberately psychogeographic.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

<a href="http://infovore.org/archives/2012/07/30/ghostcar/">I wrote <em>Ghostcar</em> in 2012.</a> It's a toy I made in part to see how viscerally I'd react to encountering myself on Foursquare.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

It's like the ghost car in a racing game that shows you a high score – like in Mario Kart or Ridge Racer: an invisible car that represents the fastest time on the track.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

By contrast, Ghostcar takes me checkins from precisely a year ago on Foursquare and echoes them onto a second, secret Foursquare account. My account is called <em>Tom Armitage In The Past</em>.

</p>

<p>

What this means is: I can check into a location and find myself, a year ago, standing there too. Does that make sense?

</p>

<p>

(The terms and conditions say I can't imitate other people, but that doesn't stop me imitating myself, right?)

</p>

<p>

So there's me in the present, and also me-a-year-ago brought forward into the present.

</p>

<p>

What I learned from this is: you can very viscerally remember a year ago. I see old-me somewhere, and remember who I was in that pub with, or why I was at an event, or what terrible film I saw, or how sad – or happy – I was at any particular point in time.

</p>

<p>

It reminds me of how I'm attached to places; what my routines look like. And it's much more visceral to see it on a map – on the same platform I entered this data into – than to just get an email about it.

</p>

<p>

Again, it's all made of leftovers – leftover data, that I spat into the world a year ago. (And: I started using Foursquare properly around the same time I built this, in order to fill it with good data). Somebody else's platform. Somebody else's libraries. ghostcar itself is, other than admin interface to set it up, fundamentally invisible. And once it's running, you never touch it again: it'll continue working forever.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

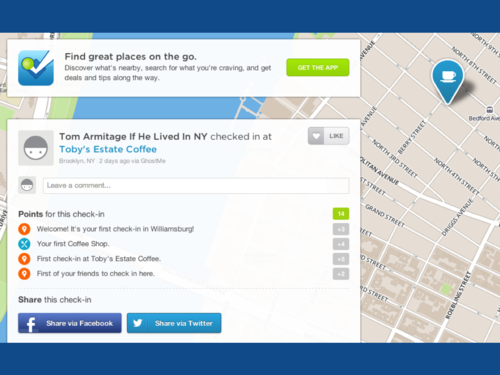

And that model – virtual copies of myself used to explore weird behaviours – continues to fascinate me. So I'm making a follow-up. I've just kicked it off recently, so consider this the first time it's ever been shown.

</p>

<p>

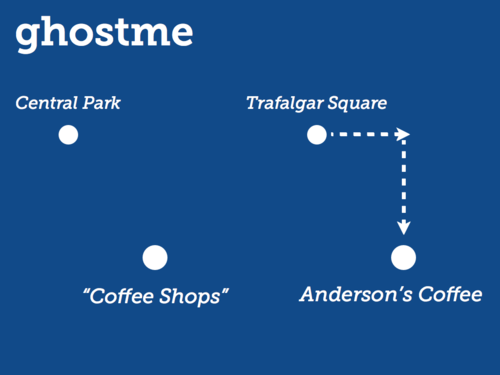

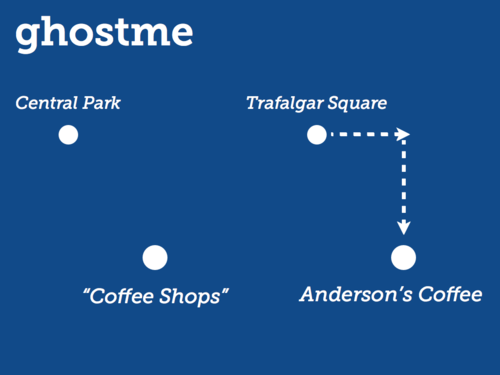

My new derivative of this is called <em>ghostme</em>. Ghostcar displaced me in time – a year. Ghostme displaces me in <em>space</em>. It makes a copy of me that inhabits another city, and goes where I might go were I alive there.

</p>

<p>

Let me explain it more clearly. Once again, this is a Foursquare echo machine – we're taking the checkins from one account, and then reflecting them on another. Only this time we're being less literal.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

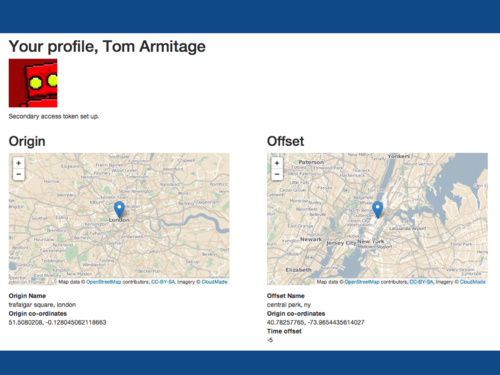

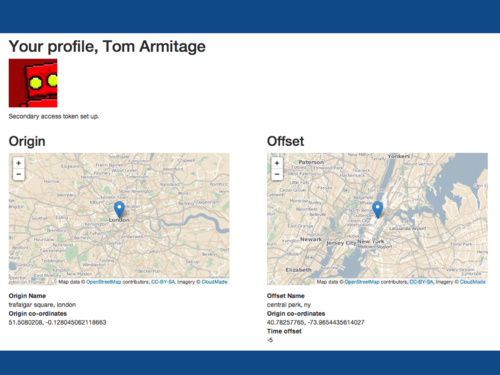

When I set up Ghostme, I tell it what I think the "centre" of my existence is. I've chosen Trafalgar Square in London. I also tell it what I think the centre of my copy's existence is; in this case, Central Park in New York.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

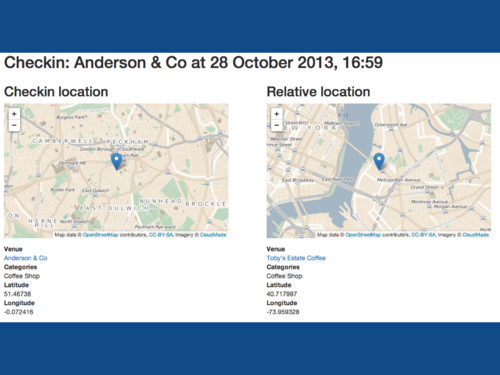

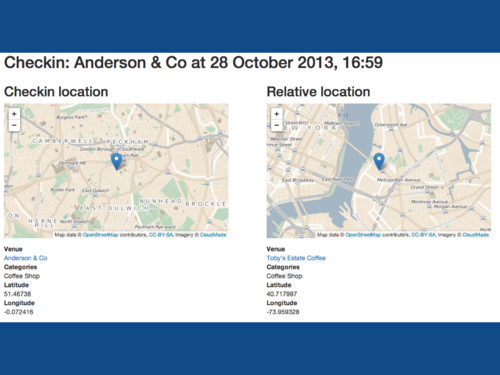

Then, every time I check in on Foursquare, the software calculates that checkin's position as an offset from my centre; applies that offset to the centre of New York; and, most crucially, then looks for all the venues in NY by that location <em>in the same category on Foursquare</em>.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

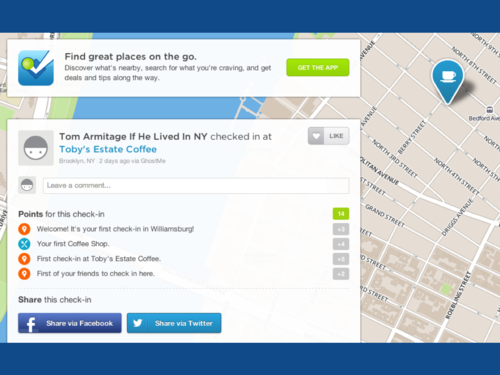

So, in this case, it takes a rather nice Peckham coffee shop, and looks for a coffee shop reasonably south and east of Central Park, and finds Toby's Estate in Williamsburg. Which is a coffee shop I rather like.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

And, five hours from now – because of the time difference – ghost me goes and checks in there.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

I wrote and tested a lot of this in a café in Edinburgh. I kept finding parallel checkins in Ontario, which I thought was some awful bug, until I looked at a map and realised no, if you go as far north from NY as Edinburgh is from London, you get to Canada.

</p>

<p>

It teaches you a lot about relative space, for starters; it also has weirder connotations, because it's less directly in your control – but when, in the case of Toby's Estate, my ghost copy goes to a place I've also been to – and that I love – it makes you grin; it's like affection for a pet or a child.

</p>

<p>

It also shows you how different the population densities and shapes of cities are – NY is, broadly speaking, quite long, especially if you consider Central Park the middle (which, given the size of Brooklyn, it really isn't). And: it reminds me how much I like that city, and how much I love the one I currently live in.

</p>

<p>

It's not been live long – and still needs polishing before I can let anyone, even friends, use it – but it's having the psychogeographic punch I wanted it to have.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

I can't talk about Psychogeography and the Situationists without talking about <em>dérive</em> – "Drift" – Debord's process for experiencing the psychogeographic procedure.

</p>

<p>

Put simply: <em>dérive</em> is an unplanned journey through the city, allowing oneself to be directed by the architecture and environment. The goal is to experience something entirely new – to expose yourself to <em>situations</em>. It is not so much getting lost as simply walking with no particular plan and being shaped by the way the environment impacts your unconscious.

</p>

<p>

Debord would point out that it was necessary to set aside both work and leisure in order to dérive successfully – to commit wholly to the task. That is a somewhat indulgent process, I'll warrant – but I reckon it still has value at a smaller, less total scale than Debord advocated.

</p>

<p>

An earlier project sought to alter and shift participants' relationships with the city they lived in.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

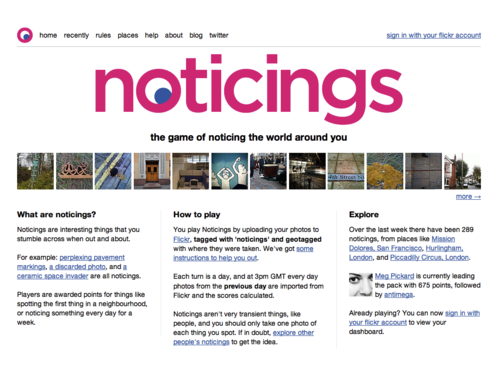

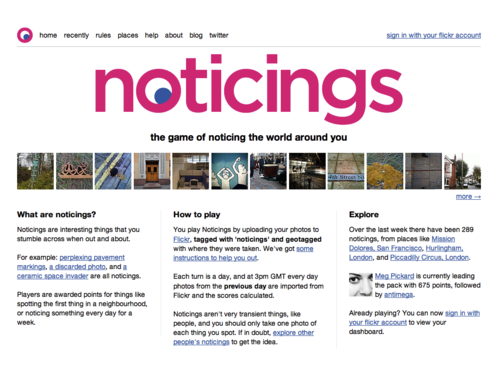

My friend Tom Taylor and I, in about 2009, noticed a lot of our friends taking similar sort of photographs on Flickr – tiny things they'd noticed in the world, not sure if anyone else had seen it, captured for posterity.

</p>

<p>

We liked that behaviour, and, more importantly, wanted to see more of it – wanted more people to look at the world like this.. So we built this tiny, almost-game, called <a href="http://noticin.gs">Noticings</a>.

</p></p>

</div>

<div class="notes">

<p>

We explained it at the time thus:

</p>

<blockquote>

<p>

Noticings is a game you play by going a bit slower, and having a look around you. It doesn't require you change your behaviour significantly, or interrupt your routine: you just take photographs of things that you think are interesting, or things you see. You'll get points for just noticing things, and you might get bonuses for interesting coincidences.

</p>

</blockquote>

<p>

Players played simply by telling the site they were playing, and tagging photos on Flickr as "noticings".

</p>

<p>

When it launched, there was one rule: you get ten points for taking a picture. Each day, we'd score the previous day's photos. And as time went on, we added new rules:

</p>

<ul>

<li>

being the first person to take a picture in a neighbourhood

</li>

<li>

your first picture in a neighbourhood</pli> <li>

taking a picture of a typo

</li>

<li>

taking a picture of something red

</li>

<li>

taking a picture near where another picture was taken

</li>

<li>

taking a picture every lunchtime for a week

</li></ul></div> </div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.019.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

And so on. It was a bit like Foursquare: some of the rules were secret, some not, and they emerged over time. Some ran for a short period of time. Here's a noticing that got points for being a noticing – and also for being something "lost" – an arbitrary judgment the player can make with a tag.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.020.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

And here's a neighbourhood, where you could see noticings within a place. Note how the scores are calculated here.

</p>

<p>

Noticings was played simply by posting picture to Flickr – it used their service, leftover data from players' photographs. It also used leftover <em>time</em> – fitting into players' routines, barely changing what they do – for some players, just asking them to use one new tag, and that's it. But it also then could encourage new behaviour, through new rules, through new bonuses – or simply because they'd enjoyed each others' pictures.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.021.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

It also cultivated a tiny bit of dérive in the day – not wholehearted commitment, like Debord wanted; but just enough – drifting off in the middle of daily routine. Or changing routine, making pilgrimages, just in order to participate, like this player.

</p>

<p>

It's exciting and weird that we changed people's behaviour like this.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.022.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

Noticings closed about 15 months later. We didn't have time to make it better, and had both just got new jobs. We closed the game.

</p>

<p>

But: people still use the noticings tag; our friends use it as a way of describing particular kind of looking. There's a little, lasting impact. And this was pre-Instagram.

</p>

<p>

Yes, for many people, Instagram is a social camera, but look at how some people use it as this tiny little social Martin-Parr-app. Lots of people are noticing, even without our little game. What was most important was that people performed the act – not that they got points for it. The fact they still are, in different ways, makes me happy.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.023.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

It's interesting for me to look back on this body of work when considering the final – and perhaps largest – project I'd like to talk about today. It takes a lot of these impulses – the psychogeographic; the act of creating situations; the act of dérive; the use of leftovers; the barely-game – and pieces them together to create a new kind of interaction that played out in the city.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.024.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

<a href="http://hellolamppost.co.uk">Hello Lamp Post</a> was a project I built along with PAN Studio and Gyorgy Galik. We entered it as a pitch for <a href="http://www.watershed.co.uk/playablecity/">the inaugural Playable City competition,</a> organised by Watershed, the Bristol arts organisation – and we won. It ran this summer for two months, and, as I look back, touches on all these ideas I've mentioned so far. Let me go in to a bit more detail.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.025.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

Watershed defined a Playable City as:

</p>

<blockquote>

<p>

"…a city where people, hospitality and openness are key, enabling its residents and visitors to reconfigure and rewrite its services, places and stories. It is a place where there is permission to be playful in public."

</p>

</blockquote>

<p>

It's a city built on the beach, not the paving stones. This is human, playful, gentle; very much the opposite of ideals about clarity, accuracy, integration, efficiency and refinement – all ideals that emerge in the prevailing rhetoric around "Smart Cities".

</p>

<p>

Worth noting, too, that the Situationists were in part resistant of the Planned City – Haussman's rearchitecting of Paris in the 19th century was very much a top-down plan. He planted fully grown trees onto Boulevard Haussman rather than letting them grow – so that everything would fit the plan. But cities are made of people, and people cannot be planned; cities require space to be organic and grow. Another harking back to the situationists.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.026.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

Anyhow. Hello Lamp Post. When we were developing ideas, a core theme kept emerging – memory and its relationship with location. We kept coming back to the idea of the city as a physical diary, based on the way that returning to places could help trigger memories. We wanted other people to see the city in this way, and be encouraged to share their past experiences and stories with each other. Making psychogeography a little more visible.

</p>

<p>

And we wanted to do that in as accessible a way as possible: for the most people, at the largest scale. I've worked around ARG-like things before, and to be honest: it's not that hard to create a cool experience for a few hundred people that's not very good value for money. Making something fun and immediate for thousands – that's far harder. But if we were to make the city playable, it had to be at the biggest scale possible.

</p>

<p>

Firstly, that meant making it super-accessible. An app for a smartphone might be cool and have GPS and that, but it limits your audience. Everybody understands SMS – <em>every</em> mobile phone has SMS – and it's super-simple to implement now; <a href="http://twilio.com">Twilio</a> does the legwork for us. Superficially unexciting technology made super-simple by web-based services.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.027.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

And secondly, to use as much of the city as possible without incurring too many costs – we'd need to use things that were already there. We wanted instead to find a way of hijacking the existing infrastructure – we spent a lot of time scouring the city for opportunities. We noticed that a lot of street furniture – lampposts, postboxes, bus stops, cranes, bridges – have unique reference/ maintenance labels. We thought it would be interesting for these objects to be intervention points – something more tangible than GPS and quite commonplace. Just telling us where you are.

</p>

<p>

At the time, I jokingly said that the Smart City uses technology and systems to work out what its citizens are doing, and the Playable City would just ask you how you are.

</p>

<p>

What we ended up with was a playful experience where you could text message street furniture, hold a dialogue with it, and find out what other people had been saying.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.029.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

This is what a conversation looks like.

</p>

<p>

We heavily "front-loaded" the experience – the first experience of Hello Lamp Post has to be <em>really good</em>. It's no good putting all the best content behind hours of play – most of it won't get seen, as a result. So we chose to make the early interactions completely fully-featured – and then treat the players who continued to engage, to come back again and again, to more subtle shifts in behaviour that were still rewarding – but that didn't hide most of the functionality from casual players. The Playable City had to be playable by everyone.

</p>

<p>

If a player played more, the game changes with them. The first time someone interacted with an object would be a bit small-talky – questions about the surroundings. But on return visits the object would appear to remember the player and ask progressively more personal questions – about their memories and points of view. The intensity grew as familiarity grew – and provided incentive to continue talking to objects.

</p>

<p>

We were building a little <em>situation</em> – creating a ritual, about talking to street furniture. A friend would tell me every time he saw somebody get out their phone and clearly start texting an object; it made me happy that we'd create this new, strange little interaction.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.030.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

To induct people into the idea, though, we needed to make it legible – it's a fundamentally invisible system otherwise. Watershed helped us with the physical advertising campaign. These were our hero objects: all these banners told you how to talk to whatever they were on, giving you the entire instructions on the poster. "<strong>Text hello banner #code to number</strong>". It was super-satisfying that the posters could all be the entire user manual for the game: you just do what they said, and off you go.

</p>

<p>

The majority of players interacted with these objects first – but many would then go on to play with other objects in the city, once they'd understood it. It helped give the invisible system form.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.031.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

We had just under 4000 players over the two month run, who collectively engaged in over 9500 conversations -speaking with over 1000 unique objects and ultimately sending 25000 messages our way.

</p>

<p>

You can see the distribution of conversations – the eponymous lampposts received a lot of attention, but so did the clearly labelled post-boxes and some of Bristols icons – such as Pero's Bridge and the cranes in the old harbour district.

</p>

<p>

Also, Gromit – from Wallace & Gromit got quite a few mentions – there were 80 giant Gromit statues all over Bristol during the summer, and people took it upon themselves to start talking to these too. Even though, you know, Gromit never says anything.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.032.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

But what was most exciting was exactly *what* people were saying; what they were sharing about their particular Bristol with others; what those moments of ritual were creating. From the poetic to the local, and the personal . And of course, because of the way the game worked, other people answering questions would see these via their phones.

</p>

<p>

And of course, the apt questions for particular objects led to particularly great answers.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.033.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

As people played, we displayed their quotations – moderated, of course – on the project website. What was great was to see just how people were engaging with the city: the kind quotations we were getting from the get go was exactly what we hoped people would say.

</p>

<p>

Now that I look back on it, I can see that Hello Lamp Post acts as a lovely summation of five years of toys and games built around cities. It's an experience that doesn't so much interrupt your experience of the city as it <em>layers on top of it</em>, letting you see the paving and the beach all at once. It builds ritual and new interactions into routine. It requires almost nothing to engage with it – and most of the systems it uses – SMS, Twilio, the city – are already built by other people. We just built the middle layer. (Which, in this case, is rather complex. But you get the picture.)

</p>

<p>

What can we learn from all this?

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.034.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

By building on top of other services, we also create a kind of sustainability. When Noticings closed, the photos were still on Flickr – just with an unusual tag. If the ghostbots break, their activity is still preserved forever.

</p>

<p>

We don't destroy the value we've created the second we turn it off. Which is more like how a city behaves: it degrades, or is reused, or gentrified, but history becomes another layer of patina on top of it – it isn't torn down instantly.

</p>

<p>

We're not planting fully grown trees and then tearing them out: we're building an ecosystem, and perhaps other games or tools will build on top of <em>us</em>. We hoped – once people twigged how Hello Lamp Post worked – they might start drawing codes on things, on posters, on street art, in order to attach messages to it.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.035.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

If the city is a beach, it is littered in driftwood. When I think of driftwood, I think about flotsam and jetsam. Flotsam is that which floats ashore of its own accord; jetsam is that which is deliberately thrown overboard from a boat – man-made detritus, as opposed to natural wastage (or wreckage).

</p>

<p>

I think those two categories also apply to the materials I'm terming "driftwood" today. And I genuinely believe the things I'm about to describe are materials, just like wood or steel. That might be obvious with regards to some of these – but not all. If a material is something we manipulate and shape as designers, then all these things could be considered materials.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.036.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

Leftover infrastructures – services like Twitter and Foursquare, more tactile infrastructure like transit networks or maintenance codes on objects. And leftover technologies, too; print-on-demand, SMS, telephony – all are now available over straightforward web APIs. These things have become commoditised and tossed overboard, made available to all.

</p>

<p>

In this way, we can spend our time working on unique experiences and interactions, rather than the underlying platforms.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.037.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

If that's our jetsam, what's the flotsam – the stuff just floating around?</p>

<p>

<b>Data</b>

</p>

<p>

The city is drowning in data.

</p>

<p>

I tend to describe data as an exhaust: you give it off whether you like it or not, and it follows you around like a cloud. People give it off; machines give it off; systems give it off. Given all the data we emit by choice – our locations stored in Foursquare, or Twitter, or Facebook; our event attendance tracked by Lanyrd and Eventbrite; as well as that we emit regardless of whether we want to – discount card usage; travelcard usage; online purchasing data – well, what are the experienes you could build around that? This is all there (with end-users permission) for the taking, and it can lead to unusual new ambient interactions.

</p>

<p>

<strong>Environments</strong>

</p>

<p>

What are the environments you can repurpose? Not just the City as a whole but smaller spaces – institutions, establishments, public spaces, parks, transit networks. All these are spaces and contexts to build within, and they all come with their own affordances. Even when they're controlled or marshalled by others, they are spaces to consider reclaiming and repurposing.

</p>

<p>

<strong>Routine</strong>

</p>

<p>

And just as we can reclaim space, consider Time as a material to be reclaimed to: what are the points of the day we can design for – not just active, 100% concentration, but all the elements where there is surplus attention? We can't create Debord's focused, committed dérive – but how can we create a tiny fragment of it, without invading the daily routines we all have to live with?

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.038.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

Because ultimately, this [above] is not the city I know. This is not More London; this is Less London. More London is this big bit of space on the South Bank by city hall, which looks like public space but is, in fact, very much not. You know it's not public because it stops you behaving like it's a city; it is doing everything in its power to resist the beach underneath.

</p>

<p>

I don't think, ultimately, the city <em>can</em> resist the beach it sits upon. There are so many things we can build atop it, be it on semi-public, semi-private, corporate spaces – or the genuine publics of the city.

</p>

<p>

To build and make them, we don't even need to invent architectures and infrastructures – we don't even have to make it obvious they're happening. We can use what's already there –

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.039.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

– making new experiences out of the driftwood that lives in the city and across the network. Lifting up the paving slabs to reveal the beach underneath.

</p></p>

</div>

</div>

<div class="slide">

<img class="slide-image" src="/talks/driftwood/img/driftwood.040.png" /></p>

<div class="notes">

<p>

Thanks very much.

</p></p>

</div>

</div></div>